Book excerpt:

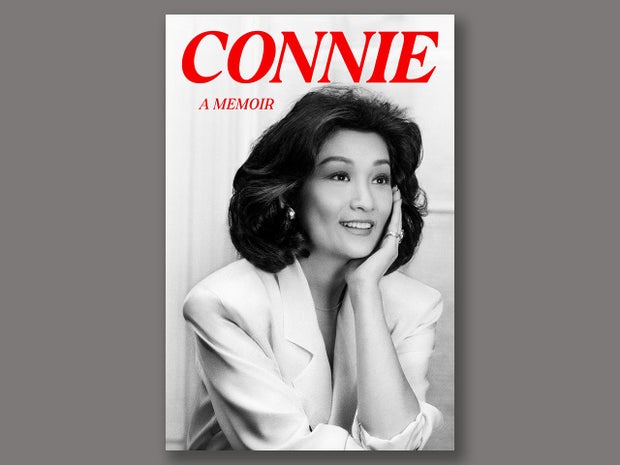

Grand Central Publishing

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

In “Connie: A Memoir” (to be published September 17 by Grand Central), veteran journalist Connie Chung writes about a four-decade career in which she broke through barriers in the male-dominated field of broadcast news, becoming the first Asian woman to co-anchor a nightly network news broadcast.

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Jane Pauley’s interview with Connie Chung on “CBS Sunday Morning” September 15!

“Connie: A Memoir” by Connie Chung

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

Good Girl/Bad Girl

Like so many working women in the 1970s, I strove to be the good girl, the Goody Two-shoes. I listened earnestly and obeyed the orders of my superiors or those who supposedly knew better. As if being female weren’t enough, I was also Chinese, meaning that in me, CBS got a double dose of obedient, respectful, and dutiful.

However, there was another side of me that the men did not anticipate, that left them puzzled. I was like the girl Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described in his poem “There Was a Little Girl”:

When she was good,

She was very very good,

And when she was bad she was horrid.

Well, maybe not horrid. Let’s say snarky.

The devil-may-care baddie (who sat on my left shoulder) would taunt the goody (who placed herself on my right shoulder) for being stuffy and urge her to say anything that popped into her head. But the good girl resisted because she knew better.

The good journalist diligently did her job. Men in politics and government at the White House, Capitol Hill, the Pentagon, and the State Department would size me up from head to toe and greet me with a look as if I were an ice-cream cone or a little china doll. Newsmakers I approached for interviews often toyed with me. When I caught up with Nixon’s Attorney General John Mitchell on Capitol Hill, he said as cameras rolled, “You look just as pretty as ever.” Did he expect me to smile and thank him? I was there to do my job and proceeded with my questions. Same with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. As I approached him with my microphone in hand, he’d flirt. There was little I could do or say to avoid those creepy old men.

But if I knew the men, I was the sassy bad girl. Before the dude could toss a sexual innuendo or racist remark at me, my modus operandi was to lob a preemptive strike. I did it to him before he could do it to me. The male would be so darn shocked, he’d laugh nervously. I am not saying my approach is advisable, but I owned it, and soon those who dealt with me knew that I could get to the bad side—faster, better, and funnier than they could. It worked. They would not mess with me when I was willing to offend first, then laugh it off.

If a man made a play for me, subtle or overt, I looked him in the eye and dismissed him. A swift “In your dreams” or blunt “Don’t even think about it.” “You are out of your league.” “You must be hard up.” A serious, quizzical “Really?” shut it down.

Never would I run to the ladies’ room crying and shaking. A toughie, I determined there was no crying in news, just the way, years later, Tom Hanks shouted at his all-female team in A League of Their Own: “There is no crying in baseball!”

Maybe someone can figure out if being the only Asian reporter was a help or a hindrance. I still don’t know. There was no doubt that the racism I experienced was as reprehensible as the sexism. Those who called me “dragon lady” or said to me, “You slant the news” or called my reporting “yellow journalism” thought they were so clever. Even men I knew would allude to my being Chinese, thinking it was funny. One referred to me as “OSE”—”Ole Slant Eyes.” Another asked, “Where are you staying? Is it near Chinatown?”

At daily White House press briefings, an Episcopal priest, Lester Kinsolving, would shout outlandish questions at the press secretary from the back of the room. He worked for various small newspapers but was considered a pesky gadfly.

One day, as I sat in the White House press room, Lester asked me, “Is it true what they say about Asians?”

I snapped back with remarkable haste, “Is it true what they say about priests?”

I don’t know what “they” say about Asians or priests but it didn’t matter, he was speechless.

Whether it was sexism or racism, I’d beat them to the punch with a self-deprecating joke. One time, CBS News Bureau Chief Bill Small said to me, “Tell them why I hired you.” I don’t know what possessed me to reply quickly, “You like the way I do your shirts.” Bill laughed uproariously. He repeated that story for years.

My approach to these derogatory remarks was the only way I could handle them at the time. It was tiresome and insulting, but I lived with it. If I’d obsessed about the issue, I could not have done my job.

In those early days at CBS, I was often saddled with light features and women’s stories like an art exhibition, toy safety at Christmas, and new orangutans at the National Zoo. I lumped it, figuring that’s what reporters had to do to earn their stripes. But there was something about covering a dreaded First Lady Pat Nixon nonevent that made all reporters, including the men, cringe. The guys refused, but I didn’t have the chutzpah to turn down an assignment.

Somebody had to cover First Lady events as protective coverage—just in case something happened. She was a nice lady, but she had a stiff, fixed smile, as if she was the long-suffering political wife which she was. Would anything she was doing really make news?

Eager to make something of what I knew was nothing, I would think of a question that might elicit a comment. Unfortunately for me, Mrs. Nixon would reply with a pithy sound bite. My reward? I was sent to cover her again and again.

On December 1, 1971, the First Lady went Christmas shopping with her daughter Julie, three months before the president’s historic visit to China. I asked Mrs. Nixon about her plans for the trip. She revealed that a friend had been teaching her Chinese. That bit of “news” made it onto Cronkite’s broadcast that evening.

About two weeks later, Mrs. Nixon gave reporters a tour of the White House Christmas decorations. Naturally, I was sent to cover it. I asked her to say something in Chinese. She laughed. “Oh no. You’re an expert. I don’t dare practice in front of you.” I pressed on, graciously but insistently. She demurred again.

What precipitated Nixon’s extraordinary China trip was a simple exchange of table tennis players between the two superpowers. Those matches were known as “Ping-Pong diplomacy”—games that thawed relations and created a breakthrough in talks with China. I did not ask to cover the visiting Chinese Ping-Pong players. I was assigned to cover them, probably because I spoke Chinese.

But later, I was also assigned to cover the arrival of the Chinese pandas at the National Zoo, a gift from the People’s Republic of China to the US. Why did that story end up in my lap? The possibility that the pandas might understand my Chinese was not likely.

When it came time for President Nixon’s historic trip to China, This time, I thought, how about if I do to them what they did to me? I will play the race card. I pushed to be sent. My pleas were for naught. Too many CBS News executives were shamelessly angling to get their names on the trip manifest. The Washington Star newspaper in DC even noted the absurdity of my absence, saying CBS was “the only network with a Chinese American correspondent, Connie Chung, [who] would seem to be a natural choice, but apparently she was shanghaied somewhere along the line.”

I watched on television as Nixon opened the doors to China after two decades of Cold War isolation. I could not help but chortle when President Nixon made an all-too-obvious comment as he stood before China’s Great Wall and declared, “I think that you have to conclude that this is a great wall.”

The president’s success in normalizing relations with China had more of a personal impact on me than a professional one. My father had not been able to write to our relatives in China for more than twenty-five years. My parents did not know who was still alive. Letters flowed again, but my parents kept what they discovered to themselves, probably because none of it was good news.

* * *

While China and diplomacy were left to experienced CBS correspondents, I was frequently sent with a camera crew on what were called “stakeouts,” in which I’d ambush someone with questions while cameras were rolling. I begrudgingly did what I was asked, even though I agreed with CBS News State Department correspondent Marvin Kalb, who took me aside one day and said, “Stake-outs are not reporting.” They were all about nabbing a sought-after interviewee, catching him off guard, and confronting him with a question he had been avoiding. It was known as “gotcha journalism.” Mike Wallace of CBS’s 60 Minutes perfected gotcha moments in which his victims would squirm.

I was assigned to “get” Deputy Attorney General Richard Kleindienst when his nomination for the top job at the Justice Department was thrown into doubt over an antitrust deal.

One day, after his confirmation hearings were gaveled to a close, I ran outdoors to link up with a camera crew. I asked Kleindienst three questions. Each time, he answered with a version of “I don’t wish to comment,” all the while smiling, chuckling, and laughing.

Not content with his non-answers, the crew and I gave chase on a raucous ride ten miles out of Washington to suburbia and the Burning Tree Club in Bethesda, Maryland. When Kleindienst ran into the golf club’s front door, I was right behind him, following on his heels. The door slammed behind him, right in my face.

Undaunted, I burst into the lobby of the club. Much to my surprise, I was unceremoniously ejected. I felt like a character in a Bugs Bunny animated cartoon being bounced out the front door, tumbling and rolling in a ball, head over heels, down the driveway. I thought I was being booted because I was an inquiring reporter. But the actual reason was that the club was the exclusive domain of men. Burning Tree remains men only to this day.

The next day, I was once again poised to question Kleindienst, this time outside the hearing room. I was pleasantly surprised when he stopped and calmly answered every question I asked. Cronkite was mighty proud of my exclusive. That night, the CBS Evening News ran three long minutes of my interview, prized real estate on the broadcast.

I always thought Kleindienst stopped to answer my questions because he wanted to reward my doggedness. Maybe not.

Some fifty years later, at our yearly lunch, Lesley Stahl, my buddy from those CBS News days, remembered that Kleindienst interview completely differently. Lesley said she vividly remembers watching my first Q and A on television with the rest of us in the CBS newsroom, when he laughed off my questions. She believed Kleindienst knew he was seen unfavorably by the public and felt compelled to rectify his behavior the next day by cooperating with me instead of blowing me off. Lesley said it was a rude awakening for all male interviewees that they had to take all reporters seriously, including and especially female reporters.

An excerpt from “Connie: A Memoir,” to be published on September 17, 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Connie Chung. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“Connie: A Memoir” by Connie Chung

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

- “Connie: A Memoir” by Connie Chung (Grand Central Publishing), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available September 17

See also: