Defence firms ‘need reassuring’ that big orders will be long-term

Saab

SaabAfter years of declining defence spending in many Western countries, the war in Ukraine since 2022 has led to a huge increase.

While Nato member states are not directly involved in the conflict, support for Kyiv has ramped up production of weapons and other military equipment.

And longer-term concerns about Russia has meant that Nato countries are continuing to increase their own armament stockpiles.

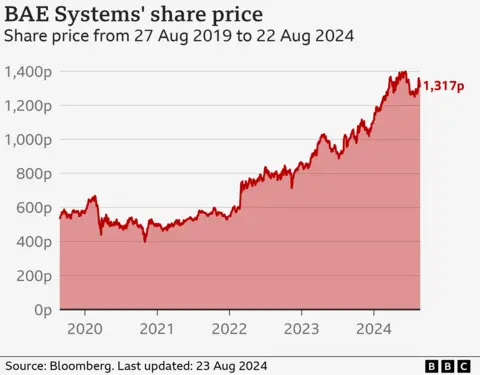

For defence firms like the UK’s BAE Systems, it has meant a surge in sales over the past three years. This month the company announced that its latest half-year revenues were up to £13.4bn, 13% higher than the same period in 2023.

Meanwhile, its order backlog now stands at £74.1bn, its highest ever. “We will keep investing in new technologies, facilities and our people, so that we can deliver on our record order backlog, and help our government customers stay ahead in an uncertain world,” said BAE’s chief executive Charles Woodburn.

But how easy or otherwise has it been for Western defence firms to increase production? And how long will the demand boom last?

To boost armament production since 2022 it has mainly been a matter of increasing output at existing factories. But this is not quite as easy as it sounds.

Many sites had only really been ticking over, if that, for years. This made expanding production not something that could be done quickly or easily.

Andrew Kinniburgh, director general of Make UK Defence, one of the industry’s trade bodies gives me an example.

“If you look at the Nlaw [a shoulder-fired anti-tank missile system] designed by Saab, and built by Thales in Belfast, they hadn’t had any new orders for many years, and the production line was basically mothballed.”

Then in 2022, Thales got a £223m contract from the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) to make thousands more over in Belfast the next four years. Going from “mothballed” to fulfilling an order of that size is quite the challenge.

The facility has more recently won a £176m order from the MoD for a separate weapon, Thales’ lightweight multi-role missiles.

“I’m incredibly proud of our Belfast workforce, who have massively stepped up to the challenge,” says Alex Cresswell, chief executive of Thales in the UK. “This has included new shift patterns, and processes being implemented to maximise working time.

“Since just before the invasion of Ukraine up to this year, just a little over two years, factory outputs have doubled. It’s doubled to the most this factory has produced in living memory. And then in the next couple of years it will double again.”

Andrew Kinniburgh

Andrew KinniburghMuch of the West’s armed forces have not been prepared for the possibility of fighting a major conflict since the end of the Cold War. The only ammunition they really use is during training, and stockpiles of weapons are very low.

A sizeable chunk of what they did have in storage has been given to Ukraine, and now needs replacing. And future stockpiles need to be much larger.

Mr Kinniburg says that Western governments are going to have to help defence firms significantly invest in both new production facilities and storage space for armaments.

Building more weapons and increasing ammunition supplies is very expensive, but Nato nations are finding the money. As the International Institute for Strategic Studies reported recently: “Overall, total Nato spending increased by 11% in 2024, compared to 3% in 2023.

Growth was even stronger among Nato’s European members, “who increased their combined military spending by 19% in real terms in 2024”, said the study.

In the UK, Kier Starmer, the new Labour Prime Minister, has reaffirmed the government’s commitment to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP, up from 2%.

It comes as Russia has significantly ramped up its arms production, and increased imports from North Korea and Iran. Meanwhile, although China denies sending Russia weapons, it does supply Moscow with “dual-use items” – those with both commercial and military applications.

Stuart Dee, research leader in defence and security at the Rand Europe think tank, says that increased military spending across Nato members is unlikely to be a temporary phenomenon. “More than two years in, the conflict in Ukraine is increasingly unlikely to be a short.

“Moreover, the security situation that emerges after the Ukraine conflict, whenever that is, is increasingly unclear, with potential security challenges across the globe. We are likely to see a sustainment of the increased defence spending across the board, as states around the globe adjust away from what has been a relatively benign period.”

But defence manufacturers do not seem convinced yet, they have spent decades being rather unloved. Mr Dee says that means Western governments are trying to persuade them they are now back in favour and will stay in favour.

“Governments are attempting to give surety, that this is a long-term supply deal,” he says. “That this is not just a two-second thing, and then you will be back to another 30 years of decline.”

Stuart Dee

Stuart DeeGovernments are trying to press home that message. Dr Cynthia Cook is a senior fellow at the International Security programme, and the head of the defence industry initiatives group at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

She says one way for governments to do this is by placing long-term orders now. “The challenge for defence firms is not really solely how long the war in Ukraine is going to last, and whether it is worthwhile investing, but who is going to pay?

“One of the signals that governments can send is to have long-term, multi-year contracts that tells industry they are going to get the money back from these investments.”

But that is not defence firms’ only problem. New investments and capacities push up costs, and the next time the government is tendering for supplies of ammunition, the company that didn’t invest to increase production, might well be able to undercut the company that did. Knowing which way to jump is difficult.

Then there is the problem of recruitment, people are wary of joining an industry that was ignored and run down until the war in Ukraine broke out. People are not exactly queuing to join an industry and devote their lives to it, when it has been in the doldrums for so long.

Even so, defence manufacturers from Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics in the US, German’s Rheinmetall, Sweden’s Saab, and the UK’s BAE Systems, are continuing to see a boom in orders. This is reflected in their soaring share prices.

Meanwhile, the FTSE All-Share Defence and Aerospace index has risen by more than half over the past year.

Cynthia Cook

Cynthia CookThen, of course, there are the lessons to be learnt from the war in Ukraine. Experts from the world’s armed forces and their suppliers are poring over the data from the battlefield.

Makers of military drones, seem to be the first major gainers from this analysis, it is a new technology which is cheap, easy to use and is having a decisive effect on the future of warfare. It is a sector where small and medium-sized companies are making a name for themselves.

That in turns means there will be more spending on anti-drone capability. No country can afford to shoot down £500 drones with missiles that cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and take months to replace for very long.

War is good for business, but it has also usually been good too for developing new technologies and weapons, and then developing the response to those new weapons.

Ukraine is just accelerating that process, if at a huge cost in human lives and misery.